Image------------ Conjuring---------Imagination--------------Magic---------------Metaphor By César Escudero Andaluz

What we are dealing with is not [virtual] reality but another representation of [virtual] reality. A representation that is so realistic that we often confuse the two. [1]

Humans have harnessed the sun’s and other rays and captured them on sensitive surfaces, creating the technical images that we call “photographs”. As a result, they appear to be on the same level of reality as their significance. What we see when we look at them are not symbols that we have to decode, but symptoms of the world through which it is to be perceived.[2]

Humans have transformed electrical impulses (bits) into visual information, as neurons do, creating the pixels we see on the screen. As a result, pixels appear to be on the same level of reality as their significance (imagination).What we see when we look at them are not symbols that we have to decode, but symptoms of the world through which they are to be perceived.[3]

Images mediate between the world and humans. They are connotative complexes of symbols that provide space for interpretation, between the elements.[4]

The images and icons displayed on a computer screen mediate between the computer screen and sighted beings.

They are supposedly maps but they turn into screens. Instead of representing the world, they obscure it. They generate new models of knowledge, until human lives end up becoming a function of the images they create.[5]

Human beings cease to decode the images and instead project them into the world, which itself becomes like an image – a context of scenes and situations. Human beings forget they created the images in order to orientate themselves in the world. “It's then that imagination becomes hallucination”.[6]

The computer becomes an image, an encoded world of scenes and situations. Users forget their relation to bits, cease to decode the code, and become a function of it. A code is a system of symbols that enables communication among people... People need codes to understand each other because they have lost contact with the meaning of the symbols. Man is an “alienated” animal. He needs to create symbols and use them to create codes in an attempt to bridge the chasm that separates him from the world. He has to try to “transmit” in order to give meaning to the world. [7]

The space of the computer is dominated by images, visual metaphors, and representative elements that mediate between the world of humans and the world of bits of information. Metaphor is based on familiarity with a prior reference. It transfers our understanding and knowledge of something that we are familiar with to something that is new, in order to help us assimilate the new environment.

Many operating systems use the desktop as an overall metaphor. It is based on users’ experience of the real world, with elements like folders, files, and documents, and actions such as cut, copy, paste, recycle, and so on. On the computer desktop, these office elements and actions connect functionality and representation.[8]

“This approach maintains a direct connection with cognitive, emotional, subjective sides. Because it presents objects from the real world, users know what to do with them. This minimises the need for memorization, allows users to decode the message of the new objects, and helps them to use and access programmes, to organise information, to reduce their effort, and to communicate.”[9]

This mental framework is inherent to human nature; it is an essential model for explaining the intuitive use of computers and making it predictable. Basing an interface on metaphor boosts the development of mental models. It helps users to remember the symbolic world that represents them.[10] As a result, computing appears to be on the same level reality as its significance.

While traditional images signified phenomena, technical images signify concepts.[11] Nonetheless, Flusser argues that all images are magical, which means that they “programme” their receivers for non-critical consciousness and “magical” behaviour that places more importance on images than situations and facts.

Interfaces reveal the imaginary side of images, and materialise the intuitions that precede it.[12] They generate a predictable environment in which users can easily interact with the operating system and software.

The user’s passive gaze is not what the graphic interface seeks; it wants users to act. At the same time, it can also transform the passivity of identification into an active function. It is essentially the dialectic play between objectivity and subjectivity.[13]

In terms of design, these metaphors must be developed and planned in line with the user’s needs and experiences. [14]

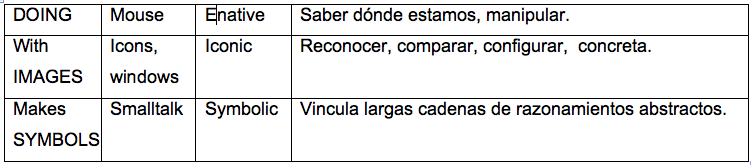

Computer scientist Allan Kay realised early on that user-friendly interface design requires a subtle understanding of the dynamics of perception. He drew inspiration from the theories of psychologists Jean Piaget, Seymour Papert and Jerome Bruner, who had studied the intuitive learning capacity of children, and the role of images and symbols in the construction of complex concepts.

As Kay put it, “doing with images makes symbols”. In other words, "doing with images makes symbols",by handling objects we can create a mental model of how things work. [15] This is the premise behind the graphic user interface.

Fig-1 Alan kay scheme.[4].

Then, in the sixties, a series of studies showed how “scalable” mentalities are, particularly in terms of the analytical problem of resolution, which is more strongly identified with Bruner’s symbolic mentality. If what we have to do is communicate, what do we communicate and how?

User interface design is critical for ensuring the success of this new way of working and playing with computers. And behind this interaction, interfaces have an opaque side. In order to decode the problem raised by an interface, we have to read its position.

The graphic user interface uses a mix of traditional and digital techniques and technologies. It is a system that allows user control by means of menus and icons: a conjuring trick that plunges users into an imaginary world, by offering them efficient access to information. Lev Manovich has argued that this is how graphic interfaces mould users and generate the appearance of reality.

In La rebelión de la mirada, Josep M. Català Domènech writes that “passive observation of the metaphoric interplay of the interface creates a sense of distance” This occurs, he says, at a didactic level of the understanding of the operation of the machine. “Mathematical operations become aesthetic, and aesthetics becomes mathematical operations”.[16]

“The reference to machines is a reference to programmes. The programme that you put into a device, that thing on your desk. The device itself is of no use for anything except maybe for holding down papers. It’s a paperweight. But it can execute programmes. And what is a programme? A programme is a theory written in an arcane, complex notation designed to be executed by the machine. But about the programme you ask the same questions you’d ask about any other theory: does it give insight and understanding? The answer here is no. They’re not designed with that in mind.”[17]

The original premise of the graphic interface was to simplify the complexity of code. Its slogan was “power is making things easy”. In practice, it not only concealed the code, but also took away the need to learn it.

““In the past, the illiterate was excluded from a culture codified in texts; in the present, the illiterate can participate nearly fully in a culture codified in images.”[18]

Vilém Flusser.

- ↑ FLUSSER; Vilém, Hacia una filosofía de la imagen. Editorial Sigma. Mexico. 1990. Pp. 8-10. [virtual] ha sido añadido a posterior.

- ↑ Ibidem. p. 12.

- ↑ Ibidem. p. 12.

- ↑ Ibidem. p. 12.

- ↑ Ibidem. p. 12.

- ↑ Ibidem. p. 13.

- ↑ Vilém Flusser, El mundo codificado [Die kodifizierte Welt; 1978]. Vilém Flusser, Medienkultur, 1997; cáp. I. [21-28]

- ↑ Christian Ulrik Andersen Associate Professor at Aarhus University, Søren Pold Assoc Professor, PhD at Aarhus University January 10, 2014 Manifesto for a Post-Digital Interface Criticism Six aspects of the interface that are important to address to critically reflect contemporary digital culture.

- ↑ Josep M. Català Domènech ,La rebelión de la mirada. Introducción a una fenomenología de la interfazURL:http://www.iua.upf.es/formats/formats3/cat_e.htm

- ↑ Paola del M. Romero, Mabel Sosa, analisis de las ventajas de la aplicación de metáforas en la interfaz de usuario

- ↑ FLUSSER; Vilém, Hacia una filosofía de la imagen. Editorial Sigma. Mexico. 1990.

- ↑ Josep M. Català Domènech ,La rebelión de la mirada. Introducción a una fenomenología de la interfazURL:http://www.iua.upf.es/formats/formats3/cat_e.htm

- ↑ Josep M. Català Domènech ,La rebelión de la mirada. Introducción a una fenomenología de la interfazURL: http://www.iua.upf.es/formats/formats3/cat_e.htm

- ↑ Paola del M. Romero, Mabel Sosa, analisis de las ventajas de la aplicación de metáforas en la interfaz de usuario.

- ↑ CASANOVAS, Josep. Documento Online, consulta [10/07/2012]. URL: http://www.wikilearning.com/articulo/de_la_accion_objeto_al_objeto_accion-doing_with_images_makes_symbols/4108-3.

- ↑ Josep M. Català Domènech ,La rebelión de la mirada. Introducción a una fenomenología de la interfazURL: http://www.iua.upf.es/formats/formats3/cat_e.htm

- ↑ Chomsky, yo soy cámara cccb, Una nueva vida de segunda mano. https://vimeo.com/112808198

- ↑ FLUSSER; Vilém, Hacia una filosofía de la imagen. Editorial Sigma. Mexico. 1990. pp. 65.